The Motivation Matrix

If you’re anything like me, you’ve probably read many blogs on motivation. Most of them deal with how to motivate our students, our children, ourselves – and it’s usually about positive, intrinsic motivation. But motivation can actually be negative, or at least result in negatively engaged students/children/self.

In this blog I am going to simplify and break down the differences between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and positive and negative engagement in an activity.

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic means outside ourselves and intrinsic means coming from within. According to Dan Pink, author of Drive, humans have evolved over time from extrinsic to intrinsic.

When we were cavemen and needed to hunt for food and water, as well as protect our young and procreate, we were operating on what Dan Pink calls Motivation 1.0. We were extrinsically motivated by the need to simply survive.

In our more civilised world we operate on Motivation 2.0 – but this is still extrinsic. We have the means to survive easily, now it’s all about getting an education, working and succeeding in a relationship. From toddlerhood right through to corporate management and family life, we learn that good behaviour will be rewarded and encouraged, and bad behaviour will be ignored or punished. The external factors of reward and punishment still come under extrinsic motivation.

And now we have evolved even further than Motivation 2.0. Consider this rather well-known riddle:

A man is looking at a photograph. He says, “Brothers and sisters have I none, but that man’s father is my father’s son”.

Who is in the photograph? Even if you’ve heard this one before, you’re probably going through the motions in your head right now, and you’d be really annoyed if I suddenly wrote the answer right here1, because you just want to think about it for a moment, yes?

What is it that makes us want to solve riddles and do puzzles? There is no reward for doing them, no punishment for not doing them… so this is what Dan Pink calls Motivation 3.0, this is pure intrinsic motivation. It’s wanting that incredibly satisfying ‘a ha!’ moment when we work something out. It’s doing an activity for no reward other than the activity itself.

Let’s consider this in the context of music teachers and their students. Which of our students are operating on Motivation 3.0, pure intrinsic motivation? Not that many. They learn piano because… their parents have enrolled them! The parents want their children to have this skill. This is fine, of course! We would not expect children to have this big picture. They’re still on 2.0… so they need gentle cajoling and appropriate rewards along the way.

Adult students are far more intrinsically motivated. They learn piano because… they want to learn the piano. They want to work and progress, so they can experience a sense of mastery. My friend and colleague Susan Deas coined the phrase ‘We learn to play the piano so that we can play the piano’. So true.

And what about us? We don’t just teach to earn money! We love our jobs. How many times have you had a nightmare student that you’ve finally decided you just cannot have in your studio anymore, no matter how much they are prepared to pay you? This is motivation 3.0 at work – a desire to have satisfaction in what you do, regardless of the rewards on offer.

Engagement

Whenever we engage in any activity, we can do it positively or negatively. So, we can engage just because we want to (intrinsically motivated), or because we want the reward on offer (extrinsically motivated). Engaging for satisfaction or for a reward is positive engagement.

On the other hand, we might engage because we’re trying to avoid punishment (extrinsic) or humiliation (intrinsic) – this is negative engagement.

The Matrix (finally)

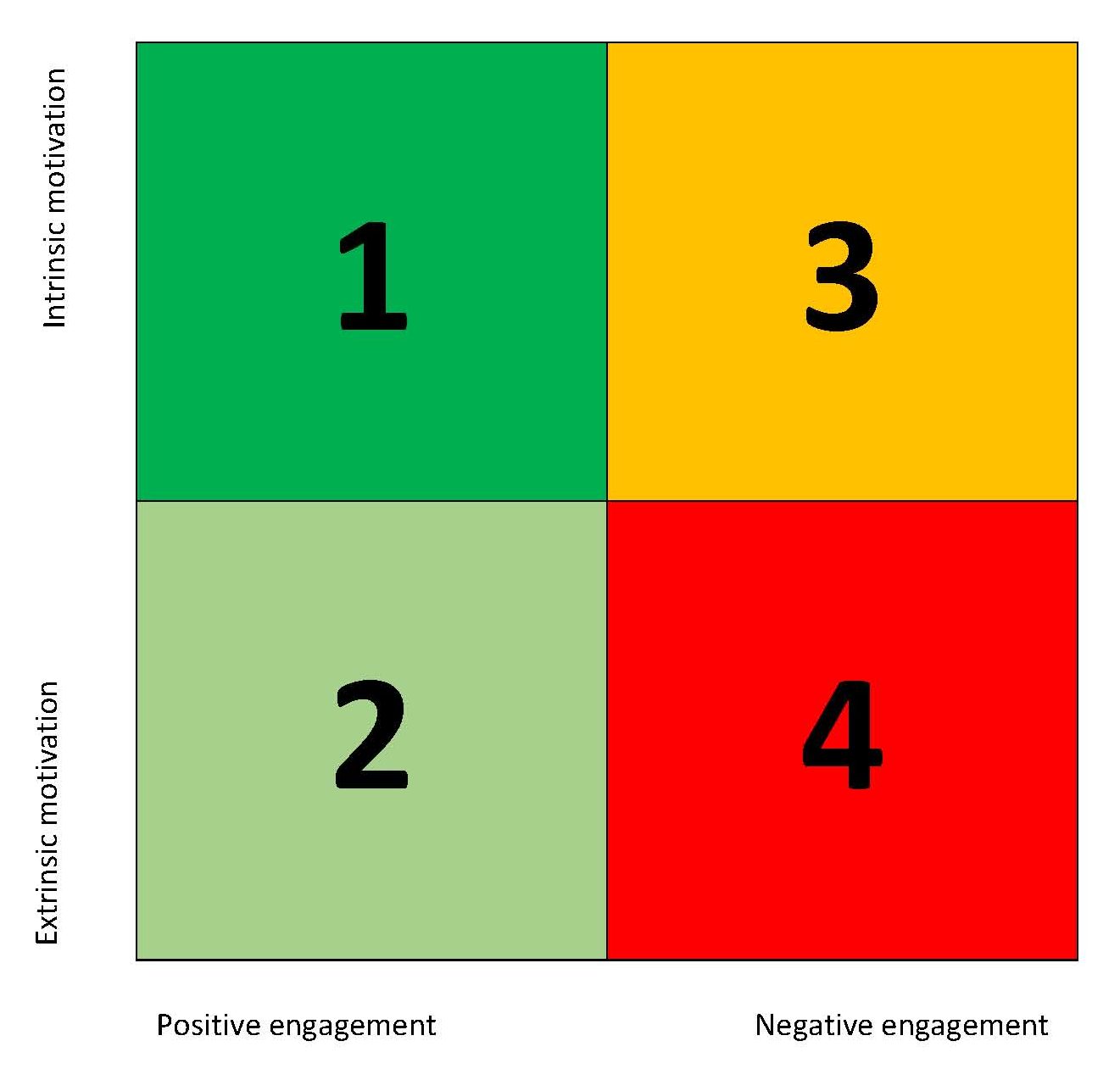

Now that we’ve talked about engagement and intrinsic vs extrinsic motivation, we can see how this motivation matrix can be formed:

Quadrant 1: Positive engagement, Intrinsically motivated

This is where we all ultimately want to be, and probably should be, as musicians. We play music because we want to. It’s got nothing to do with exams, eisteddfods, critics or fame. It’s purely for the pleasure of playing and enjoying music.

We might see our jobs as music teachers to eventually get all of our students into this quadrant. Very few start here! With the exception of adult students, who are mostly intrinsically motivated, it is rare to find a young child with aspirations of playing music for no reason other than pure enjoyment.

How to get students to Q1: We have to gently and carefully use extrinsic rewards, and well-constructed goals and incentives, to develop an overall positive experience of playing piano and eventually trigger the intrinsic enjoyment that comes from playing.

Quadrant 2: Positive engagement, Extrinsically motivated

This is where I spent most of my student life. Although I am in Q1 now, and have been for many years, I certainly didn’t start there! I spent a little bit of time in Q4 (see below) when I refused to practice at the age of five; eventually I got the hang of it and became one of those sweet, hard-working students who LOVED praise and applause and approval and getting an A+ in an exam (yay for my teacher). I was most definitely extrinsically motivated; without those goals it wasn’t enjoyable, I wasn’t playing piano just for the love of it.

It is a natural progression from Q2 into Q1, because there is so much positive reinforcement along the way, and many long-lasting skills are being developed. The only problem with Q2 is that if a student will only practice and stay motivated based on concrete rewards like stickers and chocolate, eventually that motivation will decline when the rewards go away.

How to get students from Q2 to Q1: The best way is to encourage them to perform a lot outside of exams and eisteddfods. Play for family members, go to nursing homes. The pleasure the audience gets from this is hopefully a reward in itself. Also, make sure they are excellent sight readers, and encourage them to sit down and play through old and new music books. This is also an intrinsically rewarding experience: to be so musically literate.

Quadrant 3: Negative engagement, Intrinsically motivated

It is possible to want to do an activity for sheer enjoyment but to be negatively engaged. For example, a student might:

- be desperate to learn the piano, but have no money for lessons or a decent instrument

- be taking lessons but doesn’t like their teacher or feels they aren’t getting anywhere

- really love playing but doesn’t like their pieces

- enjoy playing but feel socially isolated

All of these are examples of being intrinsically motivated to continue but feeling very negative about the experience.

How to get students out of Q3: There’s not a great deal a teacher can do if the instrument is poor quality or if there is no money for lessons. But in terms of a rapport with a student, selecting the right repertoire, or noticing a lack of motivation, we can be supportive and help the family by acknowledging/suggesting that a teacher change might work, or that taking up a band instrument would be more social.

Quadrant 4: Negative engagement, Extrinsically motivated

These are the students who just do not want to learn, or who will only practice to avoid punishment. For example: “You’re not going to that birthday party if you haven’t done your practice.” Practising to avoid missing out on a reward is also negative engagement: for example, students whose pocket money is contingent on practice will quickly fall into Q4. In fact, offering rewards of any kind to students who are already negatively engaged will perpetuate the negative cycle, because the message is clear: practice is not worth doing without a reward.

How to get out of Q4: Make sure any rewards given are AFTER the fact e.g. ‘Wow you tried so hard, here’s a sticker’ rather than ‘If you try really hard you will get a sticker’. Ask that the parents not offer rewards for practising, rather make it part of the household routine. Even five minutes is better than nothing! Also make sure there are no punishments that go along with not practising – it just makes music the ogre.

Conclusion

Understanding where each of our students are placed on the matrix goes a long way towards tailoring our approach. They are all individuals, and all bring different circumstances to their music education and potential. Our goal is having all of our students positively engaged, and eventually intrinsically motivated. It doesn’t matter if they are not there to start with; we can gently guide them there, with carefully-used rewards, encouragement, praise and support.

Thank you for this concise, straightforward, practical article on motivation. I found it really “grounding” and useful. Sometimes it is tempting to overlook the obvious!

Thanks for these excellent thoughts! I enjoyed hearing your conversations with Tim Topham (Creative Piano Teaching Podcast) and found your website afterward. You are another example of the generosity of the piano teaching community as you share your expertise, experience and wisdom with the world!

Well Marlee you’ve just made my day, thank you for your kind words 🙂

Pingback: Friday Finds #97 | Piano Pantry